Vinod Khosla is pouring his own millions into science experiments to counter global warming — and to prove he’s the smartest guy in the Valley.

Making cement without also making carbon dioxide seems impossible; the basic chemistry of the process releases the gas. But maybe that’s not really true, Stanford University scientist Brent Contstantz began thinking last year.

Of course, it was only a theory, he told himself, but the market for cement is so large — about $13 billion annually in the United States alone — and the pressure to reduce its effect on the environment so strong that he sent a 12- line email to venture capitalist Vinod Khosla.

“I have an idea for a new sustainable cement,” Contstantz wrote. “I’m sure you are already aware that for every ton of [standard] Portland cement produced, approximately one ton of carbon dioxide is released into the atmosphere. My cement wouldn’t do that; in fact, it would remove a ton of carbon dioxide from the environment for every ton of cement produced.”

Khosla, who knew Contstantz only casually — the two hadn’t been in touch for 20 years — was on vacation. But after a discussion that lasted only an hour, he told the scientist, “I don’t care about the rest of the business plan. You don’t need to estimate costs. You don’t need to do a cash flow. You don’t need to do a presentation. Just hire five people, set up a lab, and go.”

Contstantz was astonished. “What we’re up to,” he warned, “takes balls.” “Well, you’ve got the money now,” was the response. “Get busy.”

It was a classic performance from Khosla, a man who “enters any chamber believing he’s the smartest man in the room,” in the words of one longtime VC. “In 30 seconds, in one paragraph, I knew this was worth doing,” Khosla says now, adding that the cement startup, called Calera, “may be our biggest win ever.”

Over the past four years, Khosla has become the world’s foremost investor in environmental startups. He has committed an estimated $450 million of his personal fortune to financing 45 ethanol factories, solar-power parks, and makers of environmentally friendly lightbulbs, batteries, and automotive components.

These investments have made him the most prominent of an increasingly rare breed, the so-called angel investors who put their own funds into the youngest of companies — including outfits that are pursuing the most innovative, but not yet commercially viable, approaches to serious problems such as global warming. It’s a kind of seed-stage investing that traditional venture funds have largely abandoned.

And rightly so, Khosla says. “If somebody comes to you with a cold-fusion idea, you should not be funding it as an investor with other people’s money. Funding it, if they’re credible people, as a science experiment, as a hobby, is perfectly okay — as long as it’s your own money.”

Khosla’s green investing has made him something of a celebrity, mentioned in the media with the likes of mogul Richard Branson, former President Bill Clinton, Hollywood producer Stephen Bing, and General Motors chairman and CEO Richard Wagoner.

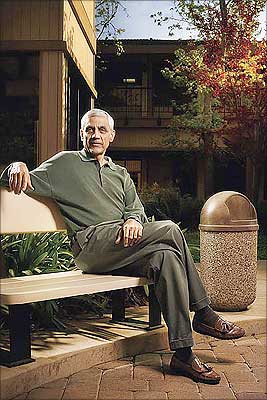

I‘ve known Khosla since his days as a recent immigrant from India more than two decades ago but hadn’t seen him in years until we met in his office in Menlo Park, California, earlier this year. Khosla Ventures is tucked away in an unprepossessing corner of a redwood complex of small offices.

The decor is rental-furniture bland. The only reading set out for visitors is a four-month-old issue of National Geographic with a cover story on biofuels. Khosla’s own office is spare, with 15 large black-and-white photographs of his four children on the walls.

For others in the firm, office dress is Silicon Valley casual — jeans, fleece vests, and running shoes — but Khosla arrives more elegantly attired, in taupe slacks; a chocolate long-sleeve, zip-neck knit shirt; and slip-ons in luggage tan with leather bows and kilties. He’s 53, a slender 5-foot-10, genial and looking relaxed despite the prominent dark circles under his eyes.

Although he lives near his office, this morning he has already driven one of his daughters to school in San Francisco, a 90-minute round-trip that he makes every weekday in order to spend time alone with her. Later, he’ll review several business proposals, prepare to announce three new investments and the hiring of an operational manager for his firm, and polish his remarks for an appearance at the United Nations.

To meet with me, he has taken a break from writing a position paper on where the world will get the biomass it needs for oil independence. He writes two or three such papers a month, averaging more than 100 pages a year. “Nobody wastes less of the time in his life than Vinod,” says venture capitalist Roger McNamee, whose office at Integral Capital Partners was for a decade just down the hall from Khosla’s, at the storied Silicon Valley partnership of Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers.

During nearly two decades at Kleiner Perkins, Khosla lost far more often than he won. He wasn’t responsible for the firm’s best-known successes of his era — Amazon, Netscape, and Google.

By my reckoning, he was most closely involved with 42 startups. Most were sold or closed, although a few still operate privately. Eleven, however, went public (mostly during the dotcom bubble). That’s better than 25% — not at all bad in the VC world.

And measured by return on invested capital, Khosla’s record has been outstanding. His half-dozen best deals at Kleiner Perkins multiplied $314 million in investments into $15 billion in cash and stock — an increase of nearly fiftyfold, and five times more than all the money invested in all 42 companies.

It was at the peak of his success in late 2000 and early 2001 — when Fortune named him the “most successful venture capitalist of all time” and he later appeared on the covers of two other national business magazines in a single week — that he decided to change.

Shares in his most successful company, Juniper Networks, were trading at more than 40 times their offering price a year and a half earlier. But he foresaw a bleak near future for optical networking equipment, in which he had made his name.

Just as telecom stocks, including Juniper, were reaching all-time highs, he warned in a keynote at a Goldman Sachs conference that at least one of the industry’s most famous companies would soon be bankrupt. “If I really believed what I was saying, I told myself, then it was time to look elsewhere,” he recalls.

Around that time, a friend introduced him to a space-research scientist with a business idea unlike any Khosla had considered before: generating electric power from water, oxygen, and natural gas.

Seven years later, the company, now known as Bloom Energy, has yet to introduce its first product, but Khosla marks his initial support for it as a turning point in his career. “I knew then I wanted to go green,” he says. In 2004, he struck out on his own. “I felt that energy needed more exploring than a responsible venture fund should do,” he says.

At Khosla Ventures, he has put his own money into graphics-display, data-center, and wireless technologies, but environmental startups are what excite him. He has been on a campaign to end American dependence on petroleum since oil was trading at a quarter of its present price.

Unlike his more famous former partner at Kleiner Perkins, the energetic John Doerr — who has choked up onstage recounting his daughter’s worries about climate change — Khosla is unemotional about going green. He hopes to improve the world by developing, for example, cleaner-burning coal and cars that run leaner, but his more fundamental motivations seem to be the size of the potential market and, even more important, the intellectual challenge of intractable problems.

Some Khosla Ventures deals are so preliminary that even he calls them “imprudent science experiments” rather than companies. “Science experiments are key to solving the problems of global warming and energy independence,” he says.

“Incremental approaches will not work.” He has backed a company developing automobile injection systems that could double the fuel efficiency of gasoline engines, if its technology works. He has millions riding on efforts to make fuel from materials other than corn, although none has advanced beyond the pilot or demonstration phase.

He has put money into a company that believes its microbes, which can turn sugar into the basis for a malaria drug, also can turn it into cheap substitutes for gasoline — and he did so long before the founders had figured out what the company’s product would be. “We’ve funded an incredible number of things that would make no sense at all for a traditional venture fund,” he says.

Khosla has long seemed drawn to venture capital by the chance to satisfy his curiosity and to demonstrate that, whatever the question, he has the answer. “I’ve never been interested in business, surprisingly,” he tells me.

“I‘m a techie nerd. What I like is intellectual stimulus. It’s fundamentally what I enjoy.”

He was smitten by Silicon Valley as a teenager in New Delhi in the 1970s. Every week, he would rent and carefully read worn-out copies of what was then the startup publication of record, Electronic Engineering Times.

In the 1990s, he was inspired to concentrate on optical communications while reading books on the physics of optics — during a vacation in Hawaii. On another typical summer break, he studied complex systems at the Santa Fe Institute; to prepare, he worked for six months with a tutor, brushing up on calculus and linear algebra.

When he got interested in climate change, he prepared an extensive briefing book for himself, loosely based on Danish political scientist Bj?omborg’s book, The Skeptical Environmentalist.

Khosla’s almost obsessive thoroughness carries over into his private life. In the late 1980s, before hiring a designer for his new 12,000-square-foot home on a woody hillside, he read more than 100 books on architecture. He likes to set goals that can be measured.

To remind himself to spend more time with his eldest child, he used to keep a jar of jelly beans on his office desk, removing one each Monday; those that remained were the number of weekends until she would go off to college. Although he travels frequently, he requires himself to be home for dinner at least 25 evenings a month; his administrative assistant monitors his performance.

Sometimes his own bookkeeping is quirky; in midconversation with me on a cell phone several years ago, he pulled into his driveway, announced that he was “officially at home,” and kept right on talking for an hour. But when I ask how often he skied last year, he answers immediately and precisely: 45 days.

Fellow investors describe Khosla as driven, arrogant, sometimes single-minded. He likes to argue and is so tenacious that his former partners often sent him into negotiations to defeat, or at least wear down, the opposition.

“What makes him invincible is that he doesn’t care if you don’t think well of him,” says an ex-partner. After Khosla expressed skepticism about hybrid cars, he responded to every last criticism of his position on the Gristmill blog. “I want to test my ideas,” he explains. “I don’t really care what they think, but one in 10 responses is something I should consider.”

“What makes Khosla invincible is that he doesn’t care if you don’t think well of him,” says an ex-partner.

Initially rejected by Stanford University’s Graduate School of Business, Khosla lobbied the dean’s office for two years, sometimes making weekly calls, until he was finally admitted. “The best way to get Vinod to do something,” says longtime friend Doerr, “is to tell him you don’t believe he can do it.”

But there is at least one skill Khosla seems to lack. As his official biography has it, while still in his twenties, Khosla helped found two extraordinarily successful startups, Sun Microsystems and an early design-automation company called Daisy Systems.

He wrote the business plan for Daisy while still a student at Stanford, but others ran the company and he soon left. At Sun, he was replaced early on as chief executive by his former roommate in business school, Scott McNealy. Khosla “had no people sense,” recalls a Sun director of that era.

“He would go through the factory floor and terrorize people and shut down the line. There was Vinod’s way and no other way. It drove his cofounders crazy.” (Khosla says that his disagreements with the board were frequent and significant but his involvement with production wasn’t among them.)

To keep him with the company, the board promoted him to chairman, but after he boycotted four board meetings in a row, sitting resentfully alone in his office, he was fired. He retained a large stake in Sun, however, as well as in Daisy, and their public offerings made him rich.

His brief, troubled tenure in the executive suite rarely stops him from telling startup CEOs what they ought to be doing. At board meetings, he’s insistent — “analytical, unemotional, and often blunt,” says one fellow director. Another describes him as “massively intrusive.”

A third, more charitably, says, “He has so much more energy than other people that he can overwhelm entrepreneurs…If Vinod’s on the board, the CEO needs a senior vice president in charge of managing him.”

As we talk around a table in his office, Khosla pulls out a laptop and runs me through one of his numerous PowerPoint presentations, flipping the slides quickly until he reaches a diagram of possible remedies for global warming. “I get so many proposals that unless I have in my head what areas I will be interested in ahead of time, it doesn’t really work,” he tells me.

He’s a tireless promoter, speaking at dozens of conferences a year. To contrast himself with Al Gore, now a member of Kleiner Perkins, Khosla likes to focus on what he calls “solutions, not problems.” The presentation he shows me, his favorite, is entitled “Mostly Convenient Truths From a Technology Optimist” — among them that global warming is “a technology crisis, not a resource crisis” and that solutions to large problems require “a dash of greed.”

To mainstream environmentalists, some of his views are heretical. He contends that hydrogen fuels are a dead end. Although he drives a hybrid car, he believes that hybrids won’t significantly slow global warming. And he’s convinced that, in most places, energy from solar panels will for many years be much too expensive.

“There are only four problems with global warming,” he tells me, “oil, coal, cement, and steel. If we do those four, we’re done.”

Done, however, is for tomorrow. Despite his ambitious plans and hundreds of millions of invested dollars, Khosla’s companies are still in the early stages. Calera is typical; it is only now preparing to open its first cement plant, on a 200-acre site next door to a gas-fired electric-power utility.

Carbon-dioxide-laden exhaust from the power plant will be captured and used to make and dry the cement. Calera plans to be in pilot production by the end of the year, in commercial operation by 2010, and running 100 sites in North America five years later.

As our meeting comes to an end, Khosla closes his laptop and heads back to work on the biomass paper. An academic is helping him with this one, which he hopes will be accepted by Science or Nature, the prestigious scientific weeklies. “Think of it,” he says as he turns away. “Publication in a peer-reviewed journal. What other venture capitalist would even try to do that?”

Courtesy :- FastCompany.com

Nice post! Thanks for the info… Have a nice day!

I think Khosla has got it all figured out!

Nice post! I have a question about the origin of your photos of Vinod – specifically, the first one.

Is there a way I could send you a message with my inquiry? My email is lraffin@asianpacificfund.org.

Thanks!

I got it from net Lizzy.

Incredible info about Vinod Khosla. This IITian is rocking the silicpn valley.

Valuable!!!! Thanks!